Published on the 08/04/2020 | Written by Jonathan Cotton

At the border and on the street, thermal detection offers a way to identify the sick – but it’s no magic wand…

With 209 countries and territories now reporting Covid-19 cases, if nothing else, the virus is good at crossing borders. And while you likely haven’t been spending much time flying over the last week, by now most of us have seen the device-to-forehead temperature gauges being used at airport terminals around the world, as authorities employ new strategies to limit the spread of the virus.

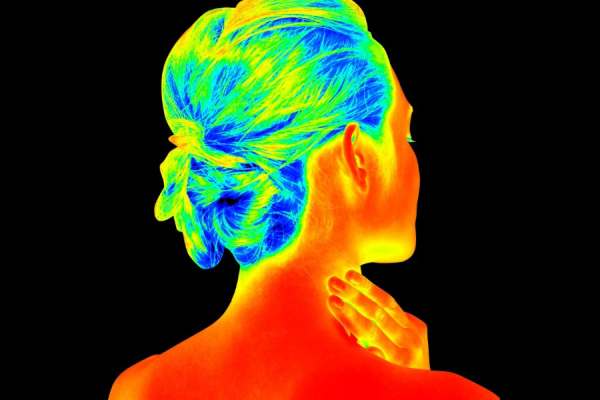

The principle is simple. One of the symptoms of Covi-19 is a high fever. As a person’s temperature increases, the amount of radiation they emit increases. Thermal detection devices offer a way to detect such variations. Such thermal scanning can be done, either by way of single-person hand-held infrared devices (think glorified pizza oven temperature checkers) or thermal imaging cameras that can check large groups of people simultaneously and at pace.

“People who have a fever before departing are probably quite rare.”

We’ve seen the technology before. Thermal imaging was used by South Korea to screen passengers during the 2002 SARs epidemic and now airports around the world are rushing to roll out similar systems.

Airports in Italy have been screening passengers for temperature. Milan has had it for a month, and similar precautions are now in place in Venezia airport and Naples’ international airport. Temperature screening has been introduced for both airports in Singapore and all airports in Thailand are now using thermal scans. Turkey is using thermal cameras at all its major airports, as is Delhi airport, Abu Dhabi and Dubai (the latter screening passengers on direct flights from China). Thermal cameras, both hand-held and fixed, are installed at all airports in Trinidad and Tobago and the Philippines has thermal scanners at three of its international passenger terminals.

Mass screening passengers based on their body temperature, performed at speed, across masses of people, without delay, discomfort or even close contact? What’s not to love?

And with applications in transport, industry and many types of public spaces – and with actual devices ranging in price from a few hundred dollars to tens of thousands – there’s clearly a market there: Omnisense CEO Leonard Lim says they’ve sold out and Thermoteknix says it’s increasing production to keep up with demand.

“Enquiries are being received from airports, hospitals, schools, large employers and places where large groups of people tend to congregate and where cross infection tends to pose the highest risk,” says the company. “We are committed to meet the challenge for providing mass fever screening.”

Brisbane-based Bigmate has produced its own thermal-imaging solution aimed squarely at employers. When positioned near an entrance or a hallway, the product – known as ‘Thermy’ – can detect multiple parties with elevated temperatures simultaneously and in real time.

“With Thermy, organisations can create a pre-screening detection system to identify people with skin-elevated temperatures, which in turn minimises the risk of impact to workplace environments,” says Mark Shield, Bigmate’s managing director.

Shield does offer some caveats however: “Thermy is not intended to be a medical apparatus. It is observational technology but it is designed to play a critical role in helping organisations speed up their ability to protect workers and their families in the fight against highly contagious virus outbreaks such as COVID19, the everyday day flu and beyond”.

So why isn’t New Zealand using thermal screening of incoming passengers? Currently international arrivals are met by health staff with paper isolation registration forms, which are then processed by Healthline, who follow up later with a phone call. (An alternate, consent-based phone tracking system for new arrivals has also been put in place but is proving problematic – of the 6250 consent requests that had been sent, only around 3000 had been returned.)

The fact is, these sorts of thermal imaging initiatives haven’t yet been shown effective for combating the spread of Covid-19. After all, the virus is highly contagious even before symptoms such as fever begin to show. No temperature means no positive ID of an infected person using a thermal detection device. Certain medications, such as aspirin, can lower fever and others can raise it. Temperature is simply not always a good way to detect who is and is not carrying a virus.

Indeed, a February study from the Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of thermal passenger screening for 2019-nCoV infection at airport exits, finds limitations with thermal imaging approaches:

“In our baseline scenario, we estimated that 46 percent of infected travellers would not be detected, depending on incubation period, sensitivity of exit and entry screening, and proportion of asymptomatic cases,” says the report.

“Airport screening is unlikely to detect a sufficient proportion of 2019-nCoV infected travellers to avoid entry of infected travellers.

“We find that exit or entry screening at airports for initial symptoms, via thermal scanners or similar, is unlikely to prevent passage of infected travellers into new countries or regions where they may seed local transmission.

“Despite limited evidence for its effectiveness, airport screening has been previously implemented during the 2003 SARS epidemic and 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic to limit the probability of infected cases entering other countries or regions.”

Associate Professor Patricia Priest, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, says that, while screening arriving travellers in New Zealand ‘seems intuitively like a good idea’, Covid-19’s extended incubation period complicates things.

“If the infected person (who doesn’t yet know they’re infected) travels during that two to 10 day period, they will not have a high temperature on arrival at a NZ airport and so will not be detected with thermal imaging,” says Priest.

“It is worth bearing in mind that people who are sick are generally less likely to travel, so people who have a fever before departing are probably quite rare. So the people who could be detected by thermal imaging at the airport are the very small proportion of infected people who move from not having symptoms to having symptoms, over the period that they’re on the plane.

“This is why thermal imaging is not actually particularly useful for border screening, in most circumstances.”