Published on the 10/08/2017 | Written by Donovan Jackson

New data-science-as-a-service provider talks data, drudgery and why software isn’t the answer…

A Wellington start-up is offering data science services to help companies take advantage of the latest darling of the tech industry. Intela co-founder Asa Cox told iStart that the opportunity the business spotted is “The lack of data scientists in New Zealand – that’s actual ones, not those who claim to be data scientists, but are really BI software specialists.”

More than that though, it’s a good example of how, to bastardise Lord Tennyson, ‘the old order changeth, yielding place to new’. Intela is providing services which a decade ago probably weren’t even conceptualised, adding high paying jobs to the economy, while also driving out properly unpleasant ones.

The distinction for a ‘real’ data scientist isn’t all that hard to make, Cox pointed out; in fact, it comes with three little letters which the BI tool guys and gals probably don’t have: an actual PhD in actual data science.

Cox explained that data science is an activity and not a product. “It is a scientific process, that is why we talk about a lack of data scientists. Data science can’t be delivered as an on-tap service like software is, but models and algorithms can be treated in that way to an extent.”

Automation…or AI

That’s another distinction he makes: ‘on tap’ AI as a service from the likes of, say AWS or Azure, doesn’t necessarily fall into the definition of ‘true’ AI. Instead, it is more like automation, targeted at solving generic problems. “That means there isn’t a huge amount of intelligence,” Cox said, echoing recent comments by Nick Whitehouse on the topic. “Also, generic solutions will do maybe 80 percent of a job, which just isn’t good enough. At that level, AWS will give it away for free.”

The nature of the just-over-a-year-old start-up’s business, with its four employees but ambitious growth targets, is diverse, including (as one might expect of a company based in the Capital) considerable government work.

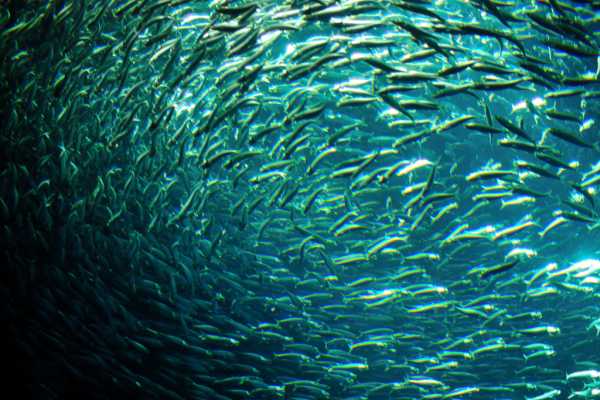

Some of that is with MPI; commercial fish monitoring has Intela writing models that allow cameras to identify species and count fish. This particular task is an interesting one, because it easily demonstrates the utility of applied data science: “This helps fishermen do what they should be doing. Right now, they have people sitting in a dark room watching videos to identify species and numbers of them to work out catch quotas. That’s just awful work that data science can do much better,” Cox said.

There’s other stuff, like master data management to get a single view of citizens; important work no doubt, but that, like the task and data automation Intela also busies itself with, is technical pap with little flash.

Starting small: data science and crime intelligence

More interesting by far, and certainly in the wake of Wynyard Group’s implosion early in 2017, is Intela’s work with the New Zealand Police, providing crime intelligence support. A bit like Wynyard? “Yes, sort of, but they [Police] have learned from that; now it’s a case of not trying to boil the ocean but to get good outcomes for intelligence then look at where data science can be applied elsewhere,” said Cox.

This is an important distinction. AI, while it has deep historical roots, isn’t commoditised. It isn’t easy to do, either (hence the PhDs). It must start small, prove itself on the little things, before moving on to the bigger ones.

But back to the cops and that Wynyard debacle. “The Police are looking for a more agile response – what Wynyard did was to overpromise. Delivering what they said they could would require a hell of a lot of tech resource and money. It just became a vicious cycle, driven in part by a background of enterprise software thinking which resulted in building a big legacy platform that was painful to implement, support and use.”

Organisations, and more specifically the people who control them, don’t want software in any event, Cox added. They want the things the software can do – the outputs – even if it takes a mindset change to realise it. “You want to own what the software does for you and companies like Microsoft have traditionally struggled with that, while others like AWS embrace it.”

And, Cox said the problems data science can address don’t have to be gnarly ones: “It could be something as simple as asking ‘are you getting enough customers’, or ‘are we efficient enough’. It doesn’t have to be ‘sci-fi’ stuff. And often, organisations might not even realise they have a problem data science can solve.”

Data science: Solution seeks problem

Which of course raises that old spectre of a solution prowling the streets looking for a problem.

Cox chuckled at that. “Yes, I suppose that’s a view, but people realise there is a fundamental shift in technology here which is not going to go away.”

More than that, “The global use cases are stacking up, even if a lot of them happen in the background, invisible. Anyone who watches Netflix, for example, doesn’t need to understand the machine learning that goes into it. People are consuming data science without knowing it and it is becoming ubiquitous, in ways that have nothing to do with the rhetoric of ‘robots taking our jobs’.”

Semantics matter: “That’s why we changed to calling it data science, it makes it more general and less scary – the scary limits people’s thinking of its utility, or how it can contribute to running a better or more efficient business,” Cox added.

The word ‘robot’, of course, derives from Czech ‘roboto’, which means ‘forced work’. While there is undoubtedly pleasure to be found in some work, there’s arguably more in watching the tedious stuff being done efficiently by software or machines. Particularly if that work involves watching endless videos of fish being hauled up from the deep.