Published on the 06/06/2019 | Written by Heather Wright

New trend has the legal fraternity in a quandary…

The fake news scourge sweeping social media outlets is being supported by a new take on video technology.

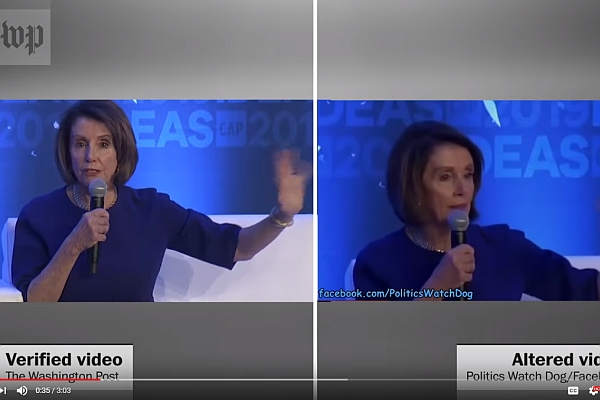

Fake pornographic videos with real (non-consenting) people, doctored videos of a “drunk” (but entirely sober) Nancy Pelosi, or completely synthesised non-existent people are part of what is being called ‘Deep Fakes’, and the trend has regulators worried.

Worried to the point of prompting the New Zealand Law Society to commission a research report into the subject: Perception Inception: Preparing for deepfakes and the synthetic media of tomorrow.

But the report is urging caution on leaping to implement new legislation to specifically address ‘deep fake’ audio and video creations, saying ‘the long list’ of current legislation should be sufficient.

The report says that a skilled person using consumer-level computing technology can create relatively realistic representations of, for example, the Prime Minister engaged in ‘entirely untrue behaviour or saying totally fabricated things’, and do so in less than 30 minutes.

Co-author Tom Barraclough says deepfake and other synthetic media will be the next wave of content causing concern to government and tech companies following the Christchurch call.

Calling for a kind of social media regulator is fine, but these suggestions need substance

“At least 16 current acts and formal guidelines touch on the potential harms of synthetic media,” Barraclough says. “Before calling for a new law or new regulators, let’s work out what we’ve already got and why existing law is, or isn’t working.”

He says enforcing the existing law will be difficult enough and it’s not clear that any new law would be able to do better.

Deepfakes – human image synthesis via AI – have been hitting the news globally, with the US House Intelligence Committee announcing last month that it will be holding a hearing on the issue amid warnings that the technology would likely be used to create fake images and videos to ‘augment influenced campaigns directed against the United States and our allies and partners’.

At Pegaworld in Las Vegas this week, Pegasystems vice president of decision management and analytics Rob Walker highlighted the increasing sophistication of AI and deep fakes. Walker provided examples of the use of AI and deep learning algorithms to create images of completely synthesised images of ‘people’, realistic video and audio recordings – with the recent video of world leaders singing John Lennon’s Imagine – and fake, but credible ‘news’ written by AI with just a simple prompt of the most basic details.

Perception Inception says with enough videos or photographs – perhaps taken from a personal Facebook or Instagram account, a skilled person could produce misleading material of everyday citizens.

To make the task even easier, last month Samsung researchers announced a new system which can create realistic deepfake video avatars from just a few images.

“This adds another layer of complexity to the discussion about misinformation and so-called ‘fake news’, privacy, identity and a further element to the possibility of foreign interference in domestic politics, already the subject of a Select Committee investigation in New Zealand.”

But Barraclough notes that not all synthetic media is ‘bad’, with Kiwi companies such as Weta Digital and Soul Machines world leaders in audiovisual effects – something that shouldn’t be stifled.

“Calling for a kind of social media regulator is fine, but these suggestions need substance,” Barraclough says. “What standards will the regulator apply? Would existing agencies do a better job? What does it mean specifically to say a company has a duty of care? The law has to give any Court or regulator some guidance.”

He says we also need to ask what private companies can do that governments can’t, noting that ‘often a quick solution is more important than a perfect one’.

“Social media companies can restrict content in ways that Governments can’t. Is that something we should encourage or restrict?”

Dr Colin Gavaghan, University of Otago Associate Professor of Law and New Zealand Law Foundation chair in emerging technologies, says not every harmful practice is amenable to a legal solution and not every new risk needs new law.

“The role law should play in mediating new technologies and mitigating their dangers is a matter that merits careful evaluation, weighing costs and benefits, figuring out what’s likely to work rather than merely look good,” Gavaghan says.

“There’s also the danger of regulatory disconnection, when the technology evolves to outpace the rules meant to govern it.”

“’Fakeness’ is a slippery concept and can be hard to define, making regulation and automatic detection of fake media very difficult,” Barraclough says.

“Some have said that synthetic media technologies mean that seeing is no longer believing, or that reality itself is under threat. We don’t agree with that. Harms can come from both too much scepticism as well as not enough.”

Image credit: Washington Post. Analysing the Nancy Pelosi fake drunk video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDOo5nDJwgA