Published on the 17/10/2018 | Written by Jonathan Cotton

The science is out: why open offices don’t foster collaboration…

Open offices and face-to-face collaboration go together like peas and carrots, right? That’s the logic, but there’s never been the real McCoy research to back it up – until recently, that is – and the results are strangely counter-intuitive.

Published by Harvard Business School in July, the study, The Impact of the ‘Open’ Workspace on Human Collaboration, is the first truly empirical study into the effects that open office architecture has on worker interaction patterns. Matching digital data from wearable devices against electronic communications, the researchers sought to quantify the real behavioral responses and organisational performance outcomes that occur from open offices, specifically in regards to face-to-face, email and instant messaging interactions.

“In general, I do think the open office space ‘revolution’ has gone too far.”

To achieve this the researchers partnered with Humanyze, a US-based company that uses sociometric ‘badges’, and the data they produce, to help companies use people analytics to improve how people work. (You may have heard of Humanyze from another sensor-based study that seemed to show that, all things being equal, women are treated differently than men in the workplace.)

The study was conducted in two parts. The first of those involved a Fortune 500 company that had declared a so-called ‘war on walls’, and saw employees moved from their traditional boundary-based seating layout arrangement (think walls, doors and cubicles) to an open office-style floor of the same size.

From there, participants were asked to wear a sensor, known as a sociometric badge, that recorded, in great detail, their face-to-face interactions, capturing a full, data-rich picture of worker interaction patterns both before and after the boundaries were removed,

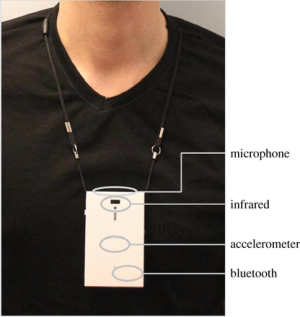

“An infrared sensor captured whom [the employees] were facing (by making contact with the other person’s IR sensor), microphones captured whether they were talking or listening (but not what was said), an accelerometer captured body movement and posture, and a Bluetooth sensor captured spatial location,” explains the study.

For the most part the second part of the study replicated the first with a longer time window. (Another Fortune 500 company in the process of a multi-year headquarters redesign, which, like the first study, involved a transition from assigned seats in cubicles to similarly assigned seats in an open office design, with large rooms of desks and monitors and no dividers between people’s desks.)

So what were the results? Does the removal of boundaries such as office or cubicle walls provoke more and better face-to-face interactions, stimulating greater workplace collaboration and collective intelligence?

Surprisingly, quite the opposite.

Researchers found that the removal of boundary walls and partitioning led to a significant decrease in face-to-face interactions. In fact, face-to-face interactions declined by a whopping 70 percent.

“Although OpenCo1’s primary purpose in opening up the space had been to increase F2F interactions, the 52 participants now spent 72 percent less time interacting F2F.

“Prior to the redesign, they accumulated 5,266 minutes of interaction over 15 days, or roughly 5.8 hours of F2F interaction per person per day. After the redesign, those same people accumulated only 1,492 min of interaction over 15 days, or roughly 1.7 hours per person per day.”

The second study repeated the results. The 100 employees tracked spent between 67 percent and 71 percent less time interacting face to face. Instead, they emailed each other between 22 percent and 50 percent more. In short, rather than prompting face-to-face collaboration, open architecture appeared to trigger a natural human response to socially withdraw from office mates and interact instead over email and IM (electronic interactions – email and IM – increased by roughly 20 to 50 percent in both studies).

“Like social insects which swarm within functionally-determined zones ‘partitioned’ by spatial boundaries (e.g. hives, nests or schools), human beings – despite their greater cognitive abilities – may also require boundaries to constrain their interactions, thereby reducing the potential for overload, distraction, bias, myopia and other symptoms of bounded rationality,” says the report.

Simply put, the study found that open-plan offices seem to create employees eager to isolate themselves as best they can (by wearing large headphones, for example) while still appearing to be as busy as possible (since everyone can see them).

“Transitions to open office architecture do not necessarily promote open interaction,” concludes the report. “Consistent with the fundamental human desire for privacy and prior evidence that privacy may increase productivity, when office architecture makes everyone more observable or ‘transparent’, it can dampen F2F interaction, as employees find other strategies to preserve their privacy; for example, by choosing a different channel through which to communicate.

“Rather than have an F2F interaction in front of a large audience of peers, an employee might look around, see that a particular person is at his or her desk, and send an email.”

“In general, I do think the open office space ‘revolution’ has gone too far,” comments Harvard associate professor and co-author of the study Ethan Bernstein.

“If you’re sitting in a sea of people, for instance, you might not only work hard to avoid distraction (by, for example, putting on big headphones) but – because you have an audience at all times – also feel pressure to look really busy. Indeed, all of the cues in open offices that we give off to get focused work done also make us less, not more, likely to interact with others. That’s counterproductive, at least given the rhetoric of open offices.

“Architects aren’t clueless to this, of course. It’s just that the cocktail of other considerations, like cost per square foot and the promise of innovative collisions, got too powerful for them to try to pull back from those extremes.”