Published on the 03/08/2017 | Written by Igor Matich

Are jobs really disappearing? Not so, argues Igor Matich; we just don’t notice the new ones…

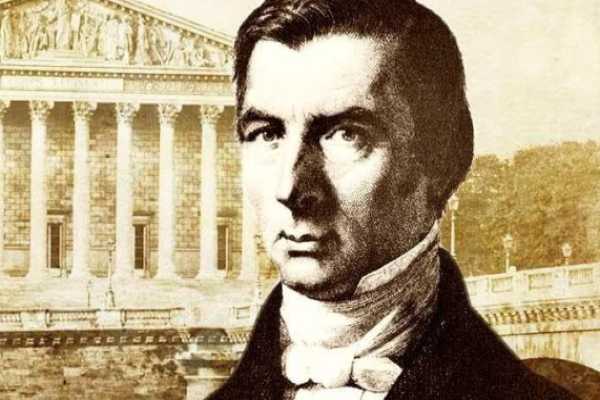

It seems odd to go back to an early 19th Century French political economist Frédéric Bastiat to shed light on current economic change, but it has great relevance when looking at unforeseen consequences. Frédéric Bastiat is noted for writing the “Parable of the Broken Window” a story which, while highlighting the unexpected flow of value, also points out that in economics, there are things which are easily taken note of, and others which are all but invisible. Bastiat’s story tells of a baker who suffers a broken window, and the townspeople who approvingly note that this creates work for the glazier. What is visible is the broken window and the money spent on the glazier to set it right. What is not visible is that the money the baker would otherwise have had to spend on anything else, is no longer available to do so. Instead, the baker must go without a new coat, and the tailor never gets to cut that cloth. The lesson from Bastiat’s broken window, and that which is easily taken note of, rings true until this day. Take a significant recent example; the news about the closure of the Cadbury Factory in Dunedin with the potential loss of 360 jobs. On the face of it, this is a great loss. It is also a highly visible one. Cadbury has been in Dunedin since 1930 and chocolate has been a part of the town, ever present with the wafting aroma of cocoa in the air. It is a tragedy which attracts the interest of newspapermen, politicians and even those without any stake in the factory or Dunedin itself. Cooler minds will note that when a factory closes, it represents the more efficient allocation of capital, if a market still exists for that factory’s output. It also releases labour tied up in unprofitable work, to be applied elsewhere (and it is inadvisable to underestimate the human capacity to do so). But what of that which is less visible? What of the jobs which are added in the regions, one by one, in more profitable pursuits, the obvious one in this case being the technology industry itself? There is no hue and cry, much less petitions. It is all but entirely unseen. And despite the next major headline of this industry or that shuttering a factory, there are hard facts which point to the ability of people to repurpose themselves and find jobs; it should be noted that ‘jobs’ in and of themselves, are not of value. Instead, the work done must address societal needs for which compensation is paid. Those facts are to be found in New Zealand’s unemployment figures, 4.9 percent at the last count in January, down from 5.1% a year earlier. There are jobs; moreover, given the advances made in mechanisation, automation and efficiency in modern times, this employment is unlikely to be drudgery – although low-paid jobs will always exist. The point is to expose the unseen. Jobs are being created. But large scale job losses make better headlines than the creation of a few jobs here, there and everywhere. Take the IT sector as case in point. The Technology Investment Network, or TIN100, has published an annual report on New Zealand’s technology sector for the last 12 years. The last report in October 2016 showed that the New Zealand Technology Sector had delivered total revenue of $9.42bn in the year up to 31 March 2016. This was up 12 percent on the previous year, the best year in the report’s history. The top 100 companies surveyed employ 40,000 people. While this report shows huge positive gains, what it doesn’t do is reveal the contribution made by the hundreds of smaller technology companies springing up all over the regions of New Zealand. They are all doing great work, much of that is unhailed as an unseen activity. Include these and the value of the tech sector would be a lot higher. With technology now the third largest export sector behind dairy and tourism, it’s arguable that we are sowing the seeds of a diversified economy, as put forward in Prof. Shaun Hendy’s and the late Sir Paul Callaghan’s 2013 book, “Get off the grass.” What we are witnessing from these changes in the economy is a transfer of value. It is an unfortunate reality that in the process, there are those who will be affected and impacted financially and socially. And yet while the duration and extent of this impact is difficult to determine, even as the carpet is ripped out from under the feet of traditional business, jobs and industries, there is growing activity in other places. Change is constant and we are entering an era where it is also becoming complicated and complex. And the evolution is only going to become more rapid with the advent of artificial intelligence, robotics and machine learning. As these technologies take effect, and in a globalised environment, New Zealand will continue to take its place at the global table, not by trying to prevent Cadbury’s factories from closing down, but through the innovation, investment and wherewithal of the unseen ‘doers’. In the big cities, and in the little ones, too. Those embracing change will win – and winning is what New Zealanders are very good at. Igor Matich is MD of Hamilton and Auckland-based cloud services and bespoke software company Dynamo6.